The British Museum

The British Museum on Great Russell Street in Bloomsbury is one of the largest and best known museums in the world, housing amongst other treasures both the Rosetta Stone and the Elgin Marbles which have been on continuous display to the public since 1817.

The story of the museum and its collectors is fascinating.

The British Museum was the first to epitomize the philosophy “this is for everyone”, later sustained in the action of Sir Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web, who gave this immense gift of internet accessibility to humanity, royalty and patent free.

Before the opening of the British Museum there was no such establishment open free of charge to the public or, as the charter read: all 'studious and curious persons'.

The original collection included Sir Hans Sloan’s “Cabinet of Curiosities”, the combined collections of some of the finest collectors of the great Victorian era of collecting, plus both his extensive and valuable library and the Royal Library of King Charles II.

As the pressures of space began to impact, many pieces of the Sloan collection were removed to the Natural History Museum where, sadly, due to incompetence, nepotism, favouritism and greed much of the orginal collection was destroyed, sold or just simply disappeared.

The 44 Ionic columns of the façade at the main entrance of the British Museum support a pediment of allegorical figures erected in 1852. These were to represent “The Progress of Civilisation” – and there could not be a more fitting analogy for what lies inside.

The 'footprint' of 92,000 sq.metres (990,000 sq.ft), plus its extensive offsite and external storage facilities, makes the British Museum one of the largest in the world, yet only about 50,000 items of the 8 million items of its collection are on display at any one time.

The inventory or works comes from all continents and traces the story of civilization from ancient times to the present.

For most of its life, the British Museum housed both antiquities and the national library – unique in the world for so doing.

The British Library is the itself the largest library in the world, currently adding 9.6 kilometres (6.0 miles) of new shelf space annually.

The pressures of growth had long since pressured both the library and antiquities collections of the British Museum so that, in 1997 the book collection moved across London to its purpose-built new site in St Pancras, leaving just the magnificent circular reading room within the Queen Elizabeth II Court of the British Museum.

The Queen Elizabeth II Great Court, generally known simply as the Great Court, is the largest covered square in Europe. It is a wonderful space and fulfils all three criteria of the design brief for the competition for its design:

- Revealing hidden spaces

- Revising old spaces

- Creating new spaces

The revelation of the hidden space is that this area of the Museum was long hidden. People were surprised to realise that in fact it occupied 40% of the total original area.

Shortly after the Museum’s opening, the concept of a glass roof over the area was inspired by Paxton’s Crystal Palace and proposed by the joint architect of the Palace of Westminster, Charles Barry. However, in the meantime, the Reading Room was constructed in the space of what was then a garden, giving no opportunity to implement the proposed concept.

The glass roof we see now was the inspiration of Foster & Partners, brought to fruition with the engineering creativity of the Italian firm Buro Happold.

It is what is called a “tessellated roof”. A honeycomb is a good example of “tessellation” as it repeats a geometric shape with no gaps or overlaps.

Overall the Great Court covers 6,100 square metres (65,659 sq ft) and this is comprised of 1,656 glass panes each of a unique dimension. There are 4,878 steel supports connected at 1,566 individually designed nodes.

The need for this clever flexibility in creating what now seems an effortlessly billowing roof was significantly driven by the slightly off-centre dome of Robert Smirke's design of the Reading Room.

There appears to be no stated reason for this, but it may be influenced by the construction of the Reading Room – considered a modern marvel in its time. According to Wiki it is actually not technically free-standing. It was built in sections over a cast iron frame with the ceiling made out of papier-mâché and suspended on metal struts.

Although it may not seem it, with a diameter of 140 feet (c.42.7 metres) the Reading Room dome is just 2 feet (c.0.6 metre) smaller than that of the Pantheon in Rome. Beneath it studied a wide list of famous people, including Lenin (who apparently signed himself “Jacob Richter”), Karl Marx, Ruskin, Rossetti, William Butler Yeats, Sun Yat-Sen, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

In fact as so many of its luminaries studied here, Mikhail Gorbachev said:

If people don't like Marxism, they should blame the British Museum.

Where before the Reading Room was only opened upon application for,and presentation of a Readers Ticket, it is now open to the general public

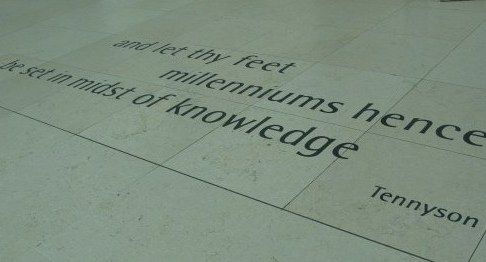

On the floor of the Great Court is this quotation from Tennyson:

The feet of the visitor to the British Museum have 2 miles (about 3.2km) of exhibition space to traverse in pursuit of the knowledge within!

One of the other benefits of the new roofing of the Great Court is that it makes a great London meeting place, and a very effective “cut-through” across Bloomsbury.

The Foster design very effectively created new spaces with the addition of the Sainsbury Galleries with their Africa collection and the Wellcome Trust Gallery with its changing topical exhibitions – usually based around the processes of life and death.

The Wellcome Trust collection is one of London’s lesser known treasures close by Euston Station, and is the site of the stupendous suspended glass bead sculpture of Thomas Heatherwick’s “Bleigiessen”.

The British Museum, though an institution, is not precious about its exhibits being “high brow”. As witness, these papier-mâché figures from South America were suspended in The Wellcome Trust Gallery during a quirky exhibition on living and dying as experienced by different cultures.

A wonderful mix of architectural eras, the British Museum effortlessly incorporates both Regency as in the Grenville Room…

…with

its refined combination of fine timber, pattern and detail

and

modern elements such as the Great

Court.

The result is a style that can only be described as, well, best of British.

Another example of the effectiveness of the British Museum’s clever incorporation of excellent modern design can be seen in the new museum shops.

Designed by the delightfully quirky London design house “Small Back Room” the four new shops each have a unique character, but are all light, airy and in themselves perfect showcases.

Some of the shop display cases create the illusion that the artwork therein is suspended between the antiquity of the backdrop environment and the reality of shiny modernity.

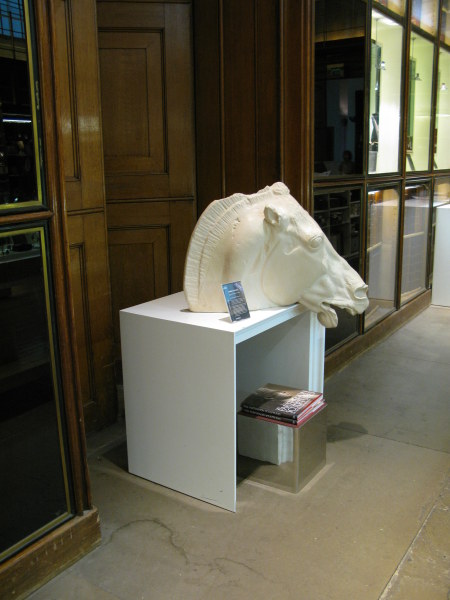

Here you can capture an ancient horse head or any one of a number of replica statues or artifacts which are set against the backdrop of the bookshelves reminiscent of, if not those actually within the marvelous library of Sir Thomas Grenville.

Seeing the horses head I was reminded of the Steven Wright comment that he had been to the museum that had all the heads and arms that came from all the other museums.

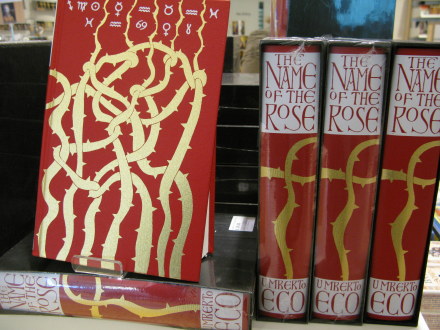

Perhaps you might purchase here a book written in Italian in 1327, by a then new author, Umberto Eco. It was not translated into English until 1983 before becoming a compelling film in 2003.

“The Name of the Rose” was the first book to combine the study of signs with fiction – and so deserves its place in the British Museum where such signs and their meaning have long mean investigated. The British Museum conservation teams have been key to restorative and interpretive activities of many treasures of antiquity.

The editions available here are exquisitely bound.

Since the mid 19th century the museum has had one of the world’s foremost conservation facilities.

Until the 1950s when staff could attend technical courses at the London University Institute of Archeology, the museum employed top craftsmen and artisans to work in their restoration and conservation workshops.

In 1975 the Department of Conservation was formed to bring together both conservators and scientists to these painstaking and revelatory tasks.

The war memorial on the front of the British Museum commemorates the staff of the museum who were lost at war, and here is the name of one such conservator, Harry Charles Lamacraft.

A relative of mine, Charles Tandy Lamacraft and his sister Doris Fanny worked in the family manuscript restoration business. It is unclear from our family records if they were in fact employees of the British Museum or trusted contractors, although it is clear that they worked on restoration papyrus.

Harry

C. Lamacraft was a British Museum photographer, although he is better known for his exploits as a champion motor-cycle racer at

Brooklands. He finished above 10th in all 10 of his races in the Isle

of Man TT in the 1930s and won a coveted Brooklands Gold Star for averaging over 100mph in a race. During WWII he became a Navigator Sergeant with the

R.A.F. but sadly was killed when his aircraft was shot down over the Netherlands in

a mission to destroy a power plant. He is buried in Amersfoort, Netherlands.

What is very strange is that the name above on the British Museum War Memorial is that of Peter Alderton.

In 1942 in Australia, Fiona (Flora) Davis was to marry Desmond Lamacraft, son of Harry C’s brother, and the name Alderton was in her line of heritage.

Harry's life has been celebrated by his successors in the Photography deprtament of the British Library. They had a bleu plaque mounted on the outside of their studios, in hhis honiour - and using the image of the aircaraft in which he was flying over the Netherlands when shot down in World War II.

The British museum is a repository of characters and their stories, right from the founding father, Sir Hans Sloane.

It is Sir Hans to whom we owe the delights of the drink of hot chocolate made with milk. It was he who conceived the idea, having found the Jamaican cocoa drink 'nauseating' when made with water. He first sold his cocoa as an apothecary tonic and later through Cadbury’s as a powder for hot chocolate.

Collectors and benefactors alike have made the British Museum what it is today.

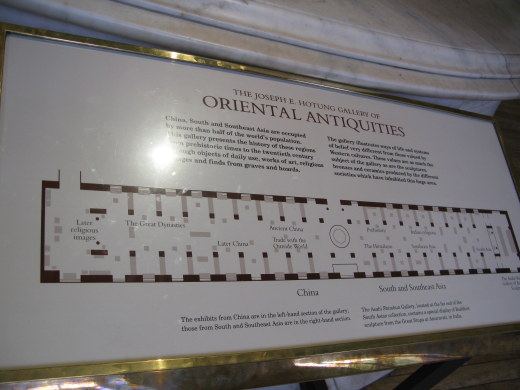

A former Trustee, Sir Joseph Ho Tung, made possible the gallery in which the extensive oriental ceramic collection of Sir Percival David could be housed .

The collection includes other oriental antiquities.

Sir Joseph’s father, Sir Robert Ho Tung Bosman, was a shrewd, well educated and charming Eurasian of mixed Chinese and Dutch descent. He rose to become one of the most influential (and richest) men in Hong Kong in the 1800s. Being naturalised a British citizen in 1888, meant that Sir Robert no longer had to carry a certificate signed by the Governor of the colony of Hong Kong when he travelled abroad, stating that he had Dutch heritage.

Sir Robert was a major financier to the revolution led by Dr. Sun Yat-Sen that led to the establishment of the Republic of China on what was then the island of Formosa, now Taiwan.

Sir Robert himself bequeathed a magnificent library. This was for the benefit of the people of Hong Kong.

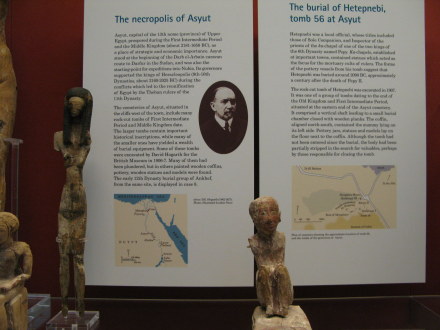

I found myself staring at a variety of mummies and their sarcophagi…

…and ancient coffins, together with their carved escorts to the underworld.

It seemed that our ancestors were as fascinated as we are today with the ancient burial chambers and their contents – and what these reveal about lives hard to imagine from the viewpoint of our time.

Here are gathered beautiful silver artifacts….

…and ancient cauldrons.

These simple but beautifully crafted items of everyday life reveal high sophistication in the civilisations whose ancient lifestyle is long lost.

The bas-relief carvings that protected the tombs must have been a challenge to the tomb raiders to bring safely across the world to rest in the British Museum.

The

rear entrance to the museum was designed not to be a public entrance, but is instead the entrance to the Edward VII Galleries, and was intended to front an avenue for victorious marches, with the saluting terrace above the lions.

FOr the wonderful lions we must than their cretor, the sculptor Sir george Frampton - whose Peter Pan graces a park in St. John's , Newfoundland in Canada.

From the rear entrance Oriental art is announced by a massive statue on the staircase that lead to the display

In the spirit of its inaugural principles, that was to make its collections available to all, the British Museum offers an elegant and efficient ‘Print on Demand’ service.

You can select from museum images, choose the paper and frame, pay, and have the finished print shipped directly home, making the collections truly universally accessible.

The British Museum is in fact a collection of collections. Researching the benefactors after whom galleries are named is as much an adventure as exploration of the collections within. The collectors were the larger than life characters of an era of collecting that was characterized by wide travels to then remote and exotic lands, and by the gentlemanly evoke compelling stories the extraordinary lives of and their collections.

The museum was founded on the collections of Sir Hans Sloane, who developed a passion for botany as a child, and in the course of his professional medical career expanded his collections with his travels.

Royal Physician to three sovereigns, Queen Ann and both George I & II, Sloane was the first physician to ever receive a hereditary title when dubbed a baronet in 1716. He was for sixteen years the President of the Royal College of Physicians, and succeeded Sir Isaac Newton as President of the The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge. This is known to us today as simply 'The Royal Society of London', which is the name on its Royal Charter, received in 1660 by King Charles II.

To do justice to the British Museum requires a lot more than this short page: Its columned entrance draws even those who are not museum buffs to explore the things that civilisations around the world have used and made to help interpret and decorate their lives over the passing centuries.

I recall what a famous modern architect has said about museums.

This was Renzo Piano, the Italian architect voted in 2006 by Time as one of 100 most influential people in the world - and in the top 10 influential people in arts and entertainment.

Of his works a critic said "...the serenity of his best buildings can almost make you believe that we live in a civilized world”.

He, like me, seems to have felt that one shouldn’t approach a museum with a rigorous agenda but instead let the place work upon you.

For me I do that section at a time. This page reflects only the oriental collections, new shops and the wonderful Great Court.

Letting the museum tempt me onwards is perhaps the mark of a person who is not a true museum buff.

Instead of a rigorous plan made before a visit to a museum I prefer to sample them. I wander and explore, and never more so than when visiting the British Museum, for as Renzo Piano said:

A museum is a place

where one should lose one's head.

One hopes he didn’t mean it literally.

AUTHOR’S NOTE:

This page draws on a marvellously written (and very British) article by Jonathan Glancy in The Guardian in 2000 just prior to the opening of the Great Court.

Research is in itself an adventure of discovery, and when you find such a well-written, charismatic summary of a place it is a real delight.

If you, too, enjoy delightfully acerbic yet evocatively informative writing, here is the link

Other London Pages