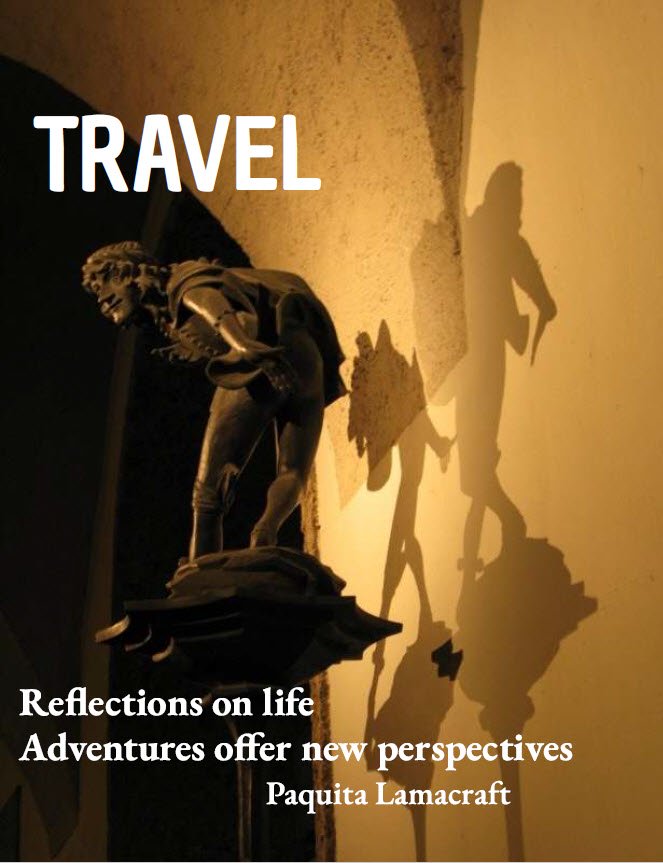

Bergamo Alta

Condolences to everyone in Bergamo because every family lost someone dear

when Bergamo became the hardest hit area of the world by Covid 19.

Deaths overwhelmed the system and military trucks had to carry corpses

without funeral to other provinces for burial.

This leaves a scar of sadness that we should all feel.

Bergamo Alta-ancient city

I visited in 2012 and felt that this city epitomised so much of Italian culture and the bonds of family and creativity in everyday affairs.

Just one hour from Milan, Bergamo Alta is a magnificent rocky town perched atop the highest of several hills. Funicular railways connect it to the lower town on either side of the mountain.

Ancient and charming, Bergamo was a powerful city in the 6th Century – one of the most influential Duchies in northern Italy.

Over time, its fortunes and allegiances have been to different seats of power, with that of the Venetian Republic fortifying the old town of Bergamo Alta with over 6000 metres of walls (19,685feet).

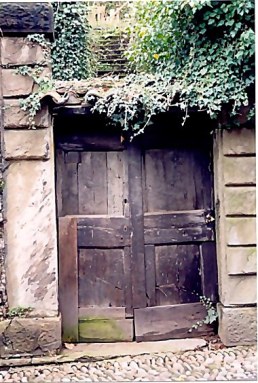

Within these walls, narrow streets twist around the steep terrain.

Restaurants are tucked under balconies.

Old doors protect stairways to villas that perch atop the hill.

The villa windows are occasionally shuttered below against intruders, or open above.

One of these tempted me with a sign saying that a studio was available.

Tiny balconies overlook the squares and streets below.

Some, with no more than a place to stand while being serenaded from below.

I wondered where the narrow alleys and hidden stairways led - and for how many centuries people have passed from public view to whatever lies beyond.

Looking back at the varying changes in allegiance in the history of Bergamo Alta, with its battles between the the Guelfi and Ghibellini, it is easy to imagine why these doors are so robustly built.These two political factions operted in the city-states of central and northern Italy in the Middel Ages and their dispute and warfare had at its core the Ivetsiture Controversay: who has the power to appoint a pope or an abbot: the Guelfi on the side of the Pope and the Ghibellini on the side of the Holy Roman Emperor.

While commonly seen as purely Italian in origin, in fact both groups had German roots: the Guelfi from the dukes of Bavaria, and the Ghibellini from the southern part of Bavaria, Swabia. The Italian dukes resisted the move of the German Emperor to control their lands.

The villas of Bergamo Alta, stacked on the hillsides or resting easily against each other along the narrow streets, rested in the soft pastel light of late afternoon, reminding me of a well-matured painting of the Old Masters .

In one of the narrow passageways two men met to chat, their silhouettes like those of ancient cavaliers.

Piazza Vecchia Bergamo Alta

The Piazza Vecchia was waiting for me.

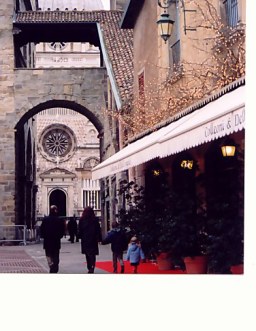

It was built in the 15th century, with an oddly harmonious mix of Romanesque, Renaissance, and Neoclassical architectural styles and is marked as being the beginning of the role of Bergamo Alta becoming the cultural centre, with Bergamo’s business centre to be left in the Città Bassa below.

On the side of Palazzo della Ragione is the Torre Civica (Civic Tower), or Campanone -the medieval bell tower.

Built over the 11th and 12 centuries, the Torre Civica was originally a tower house for a powerful Ghibellini family, the Suardi.

This was when the battle for supremacy between the Guelphi (supporting the Pope) and the Ghibellini (supporting the Holy Roman Emperor) was at its peak – and wealthy families vied with each other in a game of ‘My tower is taller than your tower’, resulting in Bergamo Alta being known as the city of 100 spires.

There is a reasonable fee, but the view from the 54 metre high tower (177 feet) is well worth it – and there is an elevator.

Bells were placed there once the city acquired the building in the 13th century, but the current bell is a newcomer, having been blessed in 1656.

In the tradition of the ensuing centuries, the bell of Bergamo Alta Torre Civic marks out the hours, striking 100 times at 10pm- originally to signify the closure of the city gates.

The 100 peels now also ring out to announce the opening of a Town Council Meeting and for the Corpus Christi Procession.

During the Corona 19 pandemic, the bells of Bergamo fell silent as the death toll rose rapidly to overwhelm the health service and the capacity to bury the dead.

There was the red carpet there as I stepped down from the tower.

I am sure it was not just for me, but accepted the gesture as a possible personal welcome to someone who would treasure the memories.

Colleoni Chapel

From the Piazza Vechia, a narrow lane drew me towards the Colleoni Chapel - built between 1472 and 1476 and finished after its founder, Bartolomeo Colleoni, had already been interred within it, a year earlier.

Bartolomeo Colleoni and the Guelph

in Bergamo Alta

Bartolomeo Colleoni was a condottiero, a mercenary military leader of the professional military companies that, from the Middle Ages through to the Renaissance were contracted by Italian city-states to lead their battles.

It was not until the establishment of the Condottieri that military science, as documented in Roman military manuals, changed the nature of warfare from being a process of chivalry – based on physical courage – to strategy and tactics to outmanoeuvre the opponent.

Himself a Guelph, Colleoni was an astute military officer and although he changed sides according to the norms of his profession of the times, he seems to have been respected both for his campaign successes and the notable lack of rape, pillage, and excessive reparations in his dominated territories.

Although he was not always in the pay of Venice, the city eventually found Colleoni indispensible, and in 1455 he became a life Captain General of the Republic.

The chapel was designed by Giovanni Amadeo - who also designed the Milan Cathedral. It is dedicated to the three saints, Matthew, Mark, and Bartholomew and was designed to be also a mausoleum for Colleoni and his much loved youngest daughter, Medea, who died in 1470 at the age of 16. Colleoni’s wife, Thisbe, is also interred here.

As would seem becoming for a military leader, the rose window on the façade is flanked by two medallions featuring Trajan and Julius Caesar.

The gilded wood statue of Colleoni, forever riding in the service of Bergamo and Venice, was crafted in 1501 by two renowned Nürenburg master craftsmen, Sisto and Syri.

The statue commemorates the man for his art of warfare – though those within his own estates may better have celebrated him for his agricultural reforms.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons: Andrea Verrocchio : Equestrian statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni

Santa Maria Maggiore Bergamo Alta

The highly decorative Renaissance Colleoni Chapel, with its red, white and black lozenges, was intentionally designed to be sympathetic to the design of the adjacent Santa Maria Maggiore church

The Gothic entrance portal on the left transept of the Santa Maria Maggiore now seems to belong quite pleasingly beside the Chapel.

It is worth a wander about these striking buildings, just to try and absorb their power.

I was struck by the many angles to heaven that seemed to be illustrated.

The rounded apse is flanked by barred windows, reflecting the history of struggle for power that marked the building of these structures that we now enjoy in peacefulness.

Historic streets of Bergamo Alta

The streets of Bergamo Alta beckon you to wander - and as you wander, to think on its long history.

Thinking of the battles here in Italy in the past and the rich architectural legacy left for us to enjoy, I thought of the wisdom of another military General, Sun Tzu, who in his The Art of War wrote:

It is said that if you know your enemies and know yourself,

you will not be imperiled in a hundred battles;

if you do not know your enemies but do know yourself,

you will win one and lose one;

if you do not know your enemies nor yourself,

you will be imperiled in every single battle.

Other Bergamo Pages