Castles of Hohenschwangau

Neuschwanstein Castle in Autumn

The classic view of Neuschwanstein Castle is from the Marienbrücke, the bridge originally made in wood by King Maximilian of Bavaria for his Queen, Marie, who loved mountain rambling.

The bridge gave access to wider mountain rambles – and especially to the narrow ridge of the mountain called the “Jugend” from which there is a spectacular view of the surrounding mountains and lakes, a view that was a favourite of Maximillian II himself.

In 1855, before his early death, Maximilian had planned to have a viewing pavilion built there.

Later, the Marienbrücke was remade in steel by their son, Ludwig, when he built the fairytale castle that was to be a homage to the operas of Wagner and the romantic ideals of chivalry.

At the time of the original construction of the Marienbrucke there was just a ruin of the former castle of Hohenschwangau on the current site of the castle we know as Neuschwanstein.

This becomes a bit confusing.

Both the current Hohenschwangau and Neuschwanstein Castles were built on sites of castles of former Knights.

What we now know as Hohenschwangau Castle was actually built by Maximilian on the site of the former Schwangau Castle.

On the ruins of the former Hohenschwangau now stands what we know as Neuschwanstein, which was actually named otherwise by its creator, King Ludwig II, who called it New (Neu) Hohenschwangau. It was re-named after his death.

Keeping track of which castle replaced which, is thus a bit of a study in history.

Marienbrücke:

The famous bridge of Neuschwanstein Castle

The Marienbrücke is an engineering feat in itself, especially given the times.

The construction company which later became Klett & Co had already celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1839. It proved an appropriate choice of master engineers and has left us some fine legacies other than its brilliant engineering.

Founder Johann Klett developed many liberal socialist ideas through his exposure to them in Switzerland, Italy, and France – and this was reflected in his activities.

His son-in-law, Theodor Cramer-Klett continued the tradition with many philanthropic works, the most notable of which was his battle to establish the Nuremberg Industrial Museum. This was inspired by both the Paris ‘Conservatoire des Arts et des Métiers’ and what was then called the ‘London Kensington Museum’ – now known simply as the ‘Science Museum’.

The Nuremberg Industrial Museum project was not popular with the politicians and the battle for its establishment took place over many years and demanded considerable capital from Klett and Co to eventually succeed.

The remarkable evolution of the engineering company which built the Marienbrücke

Johann Friedrich Klett had arrived in Nürnberg in 1798 and worked in a

manufacturing establishment there. He married the daughter of the owner

who had prematurely died, and took over the firm.

Making a

business research trip to England in the midst of the Industrial

Revolution, Johann returned to establish a worsted yarn spinning works,

and later moved into railworks and steam engine manufacturer.

The

company built the German equivalent of the Crystal Palace which had been ordered by King Maximilian

II for the 1854

Munich Industrial Exhibition.

Built without any load-bearing walls and containing 37,000 windows, the massive structure was built in six months and opened five weeks later, just three years after the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London.

As

well as the Marienbrückehe, the company also built the Augsburg Main

Railway Station hall - and two lovely bridges across the Rhine in my

favourite city of Mainz, where I lived first when I came to Germany.

When

Johann Klett died, his son-in-law, Theodor Freiherr von Cramer-Klett

took over the business. His father had moved from a business importing

colonial goods to establishing a soap manufacturing plant in Vienna.

Theodor

Cramer-Klett was a financial genius, setting in place creative

investments. His financial loan model was underpinned by several banks –

and the interactions of the bankers on setting in place the financial

investment company under Klett’s name later became Allianz Insurance.

Later, fifteen years after Theodor’s death, his son would form the Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg AG (MAN)

– and move into the new field of diesel engines – and turbo-charged

engines of all sorts, which still underpin the company we now know as

“The MAN Group”.

Hence the tagline of The MAN Group:

Engineering the future since 1758.

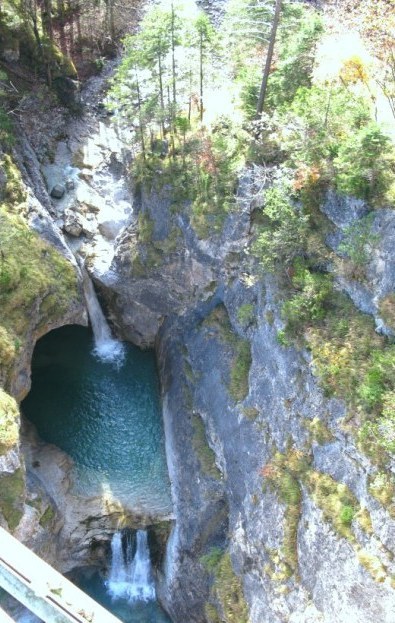

The canyon beneath the Marienbrücke

at Neuschwanstein

Underneath the Marienbrücke, the waterfall flows from 45 metres (147 feet) higher up the mountain, passing 90 metres (approx 295 feet) under the bridge.

It is not a sight for those who dislike heights!

Hoheschwangau castles and the weather

The rocky outcrop on which the castle sits contributes to its fairytale qualities, for it seems to appear magically in the landscape. However, the climate is not one of constants – and the effects of freezing winters and lashing snowstorms has eventual impact on the sandstone face of the castle.

As a result, Neuschwanstein undergoes regular repairs to the castle face itself, as was happening when I came in Autumn.

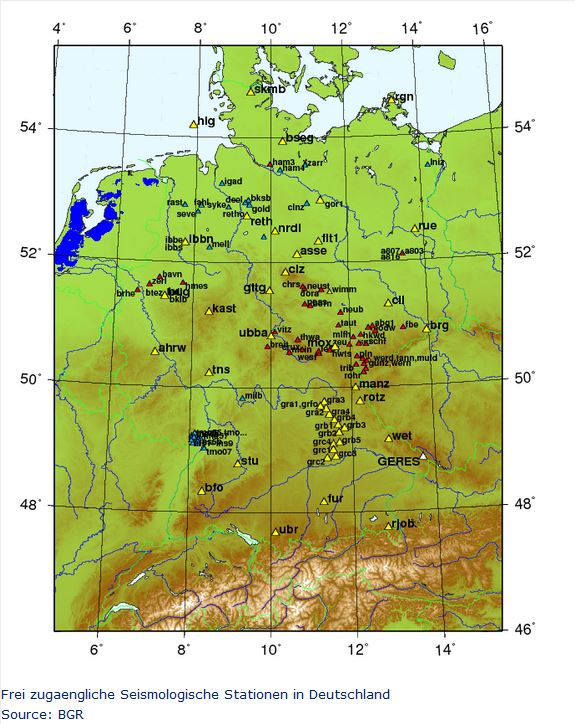

Earthquakes in Hohenschwangau

Earthquakes in Bavaria are also not unknown, and the rock face on which the foundations of Neuschwanstein stand are constantly monitored for any shifts.

In addition, the Bavaria Seismological Surveillance Network has two nearby stations: Schneefernerhaus at 2,650 metres above sea level (about 8,694 feet), and Partenkirchen at 7,60 metres above sea level (about 2,493 feet).

These are part of BayernNetz, which in turn is part of the seismological network of the greater Germany, and has 21 digital seismic stations in their network.

These measure and send seismological data to a global network: the National Earthquake Information Centre in Denver, the European Mediterranean Seismological Centre in Bruyeres le Chatel, France, and the International Seismological Centre at Newbury in West Berkshire, England.

The map of earthquakes in Bavaria and surrounding areas between 2000 and 2009 shows that our blue planet is a busy one underneath its surface.

With thanks to the German Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources, this map showing German recording stations gives a clue to the areas of most frequency, and Hoheschwangau is nicely ringed by them.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

Advance earthquake warning technology

But don't be too concerned: In addition to these measures, in 2007 at the nearby Zugspitze, a borehole was drilled into the summit and temperature sensors were installed to monitor the effects of permafrost (when soil or rock is permanently frozen).

This long term measurement project is designed to give the region advance warnings of the conditions that can cause major rock falls or settlement of mountain outcrops.

It is just as the popular Audi advertisement said – you are protected by good German efficiency with:

Vorsprung Durch Technik

The literal translation of the slogan is 'Advancement through Technology', but it is more often roughly translated as 'leaping ahead through technology' – but in this case, with the expectation that no one will have to leap.

On an unseasonably warm autumn day when I visited, the only shaking was for those too nervous to actually walk onto the Marienbrücke after the effort of getting there.

On the bus up there was a Japanese tour group, and after having had my photo taken together with my seat companion when we alighted by all her friends – one after another, I was eager to stride ahead of the man holding his flag.

With a smile and cheery wave I had been there, taken photos, and was back before they arrived.

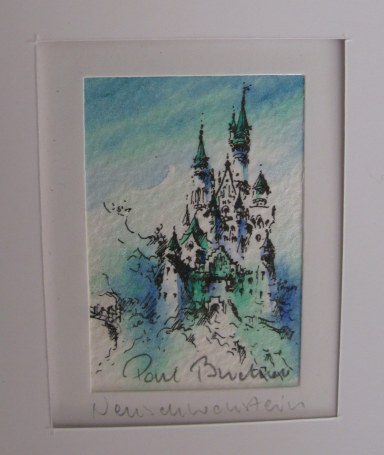

Hohenschwangau: An artist's magnet

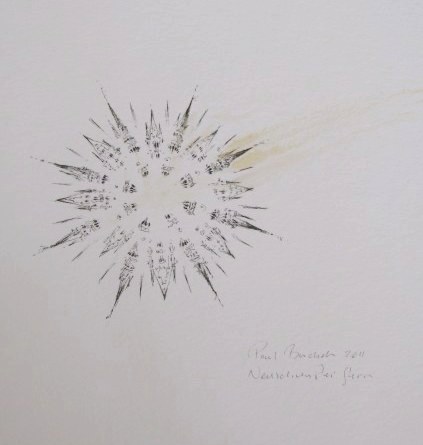

Before being caught up by my new Japanese tourist friends, I was in a friendly chat with the artist Paul Buchon. He was seated on the wall below the bridge, a little lower down.

Here, he had his lovely

water-colour-washed ink sketches set out for sale.

It is not unusual for an artist to locate himself at the site of an international icon like Neuschwanstein – but Paul’s work is exceptional.

This miniature came home with me.

I thought it deserved a nice frame and a place with my other treasured original artworks and it is now a part of my dining room gallery of small originals.

Paul Buchon’s favourite was this ink drawing with the castle turrets of

Neuschwanstein forming a star, or comet – complete with golden tail.

It

seemed something of a metaphor for the life of Bavaria’s King Ludwig

II: a blaze of extravagance – and then abruptly, his life ended.

The Alpsee below Neuschwanstein and Hoheschwangau Castles

The route to Neuschwanstein Castle from the Marienbrücke is scenic, looking down at the Alpsee through the trees.

Mountain trails at Hohenschwangau

Further along you can also see the castle of Hoheschwangau above the lake.

It is a favourite place for hikers who take particular delight in alpine rambling, just as did Marie, King Ludwig’s mother.

There are various trails – all of them tempting in their seductive autumn dress.

Neuschwanstein

Then, suddenly you are there at the foot of the castle, looking up at the towers and their details.

I found the lion on his plinth overlooking all, to be a contrary creature whose features could not quite be captured – at least not from this angle.

His stance reminded me of my regal Chow Chow Balu and how he used to sit, staring out across his own estate as if royalty itself.

In the picture below you see that the lion is featured as a regal sentinal on the left plinth, overpowered by the towers of royalty: a symbol of the fate of the two young princes of Bavaria who grew up spending summertimes here in this very castle by the Alpsee.

Looking back, I wondered again at the engineering marvel that the Marienbrücke,

in both wooden and steel forms represented.

A handy hint for the castle traveller

In the process of my autumn trip to Neuschwanstein I learned a lesson to pass on. If you go by bus to the Marienbrücke, make sure you have enough time – or like me you will miss your tour. It is quite a walk and one can become easily distracted en route from the bus stop.

There is often no capacity to rebook at the castle itself.

It requires a trip back down to Hohenschwangau to the ticket office – and possibly a long wait both in the queue and for the next available tour in your chosen language.

As a result of making this mistake I contemplated what was the best option: horse-drawn carriage up the hill, or bus and then the carriage down.

Having done both, my vote is to take the bus to the Marienbrücke and the horse-drawn carriage on the trip down.

If you go by bus you walk DOWN the rather steep hill to Neuschwanstein – an energy saving option compared with coming in the other direction UP the hill.

Just make sure you have plenty of time.

It was a bit disappointing to miss my tour, as I had hoped to photograph the view from the terrace again, but at least I had been through the castle before.

It would be a different story if this was your one chance to see it while travelling on a tight schedule.

Childish adventures at Hohenschwangau

As I wandered down to the staging area of the horse-drawn coaches, I passed children walking along the walls, held by the hand by parents in

Bavarian jackets.

It is something I enjoy in Germany – children encouraged and allowed to have a bit of adventure: some well-managed “risk”.

Elsewhere

I have lived, there would be park rangers telling the parents this was

not allowed – but Germany is a country with city parks that have

wonderful adventure playgrounds that the English or Australians would

have a fence around, if they were allowed at all.

The royal legacy of Saint George: Hohenschwangau

On the walls of Neuschwanstein, Saint George is depicted, slaying the dragon.

Saint George is the patron saint of the Bavarian Royal Family, as well as that of England, and although the English think Saint George is particularly English, in fact he is much busier than that.

Other allegiances of Saint George

According to Wiki he is also patron saint of Romania, Bulgaria, Aragon, Catalonia, Ethiopia, Georgia (the country, not the state of America), Greece, India, Iraq, Lithuania, Israel, Portugal, Serbia, Ukraine, Russia, and the Maltese island of Gozo.

I suppose for someone who is able to slay a dragon, this should seem not too arduous a list of responsibilities.

St. George the Patron Saint of cities

However, apart from these and the numerous professions and associations and types of illness who also invoke St. George, he is also Patron Saint of many cities.

The list Wiki cites so far includes: Genoa, Amersfoort (in Utrecht, Netherlands); Beirut; Al Fakiha and Bteghrine (in Lebanon); Cáceres (Spain), Ferrara(Italy) , Freiburg (Germany), Kumanovo (in the Republic of Macedonia); Ljubljana (Slovenia);Promorie (Bulgaria); Preston (UK), Qoormi (Malta); Rio de Janeiro; Lod (Israel); Lviv (Ukraine); Barcelona; Moscow; and Tamworth (the one in Staffordshire, England, not that in Australia which was named after the original).

Apparently, according to Georgian myth, St. George was cut into 365 pieces at his death in battle – and pieces were spread around the whole country. It appears by the list above, that they may have even been spread far beyond the borders of Georgia.

The myth of St. George has a multi-denominational and geographically wide-spread attraction.In the words of the cult American author Robert Anton (Bob to his friends) Wilson:

Humans live through their myths

and only endure their realities.

Nothing could have been truer said about King Ludwig II of Bavaria – the person responsible for building Neuschwanstein Castle.

More German Romantic Road Pages