Hôtel-Dieu:

Hospices de Beaune

Hôtel-Dieu or the Hostel of God in Beaune-

and why not to give chrysanthenums to your French host/hostess

The Hospices de Beaune came into my life through studying art and Shakespeare at school and then later in French language classes together with the mandatory supporting 'French Culture' class.

It was here that I was taught never to take food or wine (unless really superior and, of course, French) as a gift to the host when invited home for a meal. Instead, chocolates or a small plant are acceptable – (one wonders how many small plants a house can accommodate after years of accumulating them in this manner) – as are flowers.

These should be unwrapped before presenting and gathered in odd numbers (but never 13) - oh! - and not be chrysanthemums which traditionally go on graves. Chrysanthenums are sold in their pots by the thousands on All Saints Day La Toussaint. The tradition strated after World War I and it is generally indicative of immortality as they live through the winter. Carnations are also off the list, as some see them as bringing bad luck. Roses can have dual meaning – socialist politics or love - making what I always thought to be an interesting pair of alternate meanings – but not be yellow, for they may then indicate lovers betrayal.

Who says we remember nothing from school?

Hospices de Beaune

is a must for your list of things to see

Having seen images of Hospices de Beaune as part of this cultural induction, I found them so compelling that I put Beaune on my 'List of Things To See'.

Oddly, although I have removed many things from this list as having been visited or done, the list itself seems to grow longer rather than shorter, for there is so much to experience.

Beaune is not inexpensive (understatement)

So it was in this context that we arrived in Beaune one summer evening by car and thought we would enjoy a glass of wine and something to eat.

Coming from a wine region in Germany, where wine by the glass is very reasonably priced, we were shocked to find the escalated prices in the Burgundy region – and so went off to dine after curtailing our intake accordingly.

The meal was equally expensive. As it was a bit late, most places had closed their kitchens, so we went to a small restaurant in the centre where we ordered the most inexpensive menu item, which was a mushroom cassoulet. It emerged as something of thimble-like dimensions with a mortgage attached, with the result that the scene for realising a girlhood dream was somewhat dampened by both the experience of this expensive taster of a dinner and the ensuing hunger.

Hospices de Beaune

- refuge, art gallery and hospital

The following morning, we walked out from the hotel and almost literally bumped into the entrance for the Hospices de Beaune or Hôtel-Dieu, the Charity Hospital established by Nicolas Rolin at the instigation of his wife, Guigone de Salins.

The main hall beneath its painted beams seems a peaceful and even elegant place today.

This makes it important to reminder yourself that each of these beds was, in earliest days, assigned two occupants.

Healing the body and the soul

at Hospices de Beaune

However, the Hospices de Beaune was not only advanced for its times in the arrangements for the care of the sick and aged, but also a repository of art from the most noted craftsmen and artists of Europe.

In an advanced view of the importance of cleanliness, Rolin banned the use of wooden bowls for the patients. Instead, each person was assigned his or her own napkin, plus bowl and mug of tin, as seen here beside the bed.

A remarkable social experiment

to rectify social inequity - truly a Hôtel-Dieu

The establishment of the Hospices de Beaune was, in itself, a remarkable act of charity – but that is should be established as a place of such beauty is its most astounding identifying mark.

The need for such a hospital for the poor and needy must be set in the context of the times.

The Hundred Years War had just been successfully ended by the Treaty of Arras as a result of the successful joint efforts of the King of France and Duke of Burgundy to expel the English.

Rolin played a key role in bringing the King of France and Philip the Good of Burgundy together to heal long-standing animosity. This originated from the belief of the Duke that the King was responsible for the assassination of Philip's father at the time of a meeting between the two in Montereau. It was for his efforts in this role, and for his contribution in securing the treaty by diplomatic efforts with the English, that Rolin received extensive grants of lands and riches.

After the war ended, disbanded soldiers formed marauding bands whose brutal attacks caused villagers to leave their homes and fields and seek refuge in walled towns and chateaux. The result was famine for there was no-one farming the land.

This, together with the extensive impact of the plague (the Black Death) that had ravaged the population during the preceding century, left the region in a state of desperate poverty.

It was in this context of history that on 1 January 1452 the first patient of the Hôtel-Dieu (Hostel of God) arrived.

Distinctive architectural features

of the Hospice de Beaune

The colourful roof tiles are a hallmark of an area that ranges from Beaune to Dijon.

The patterns on the rooftops of the Hospices de Beaune made a sort of pleasing tartan that, when set against a blue Burgundian sky, made an indelible mark on my memory.

My schoolgirl French class had not disappointed me.This was truly as wonderful as it had seemed when I learned about it in an Australian school and vowed to come here.

The balconies and cornices of the various windows each have an individual character, with lovely spires above window dormers.

The roof of the chapel is less colourful, but the plainer background tiling is enhanced by a flurry of spires and chimneys, windows, and details that keep the eyes turning upwards to capture the personality of each.

It made me smile to know that above it all, a saint is watching over us.

Joan of Arc - a patriotic fiction, and

the founders of the Hôtel-Dieu

On the subject of saints, Joan of Arc’s history is closely linked with the times of the establishment of the Hospices de Beaune.

I had previously read and reported here acccordingly, that both Nicolas and his wife were keen to meet this activist, which they duly did before Philip 'the Good' handed her over to the English to be made a legendary martyr.

This followed the previously recorded the history we have all learned or read about the 'Maid of Orléans' and her martyrdom.

However, as recorded in Graham Donald's carefully researched book 'The Mysteries of History: Unravelling the truth from the myths of our past', Joan's name is incorrect, as is her supposed role in galvanising the French by leading them to battle , and of her being 'sold' for 100 crowns by Phillip the Good- as is also the myth of her being executed for witchcraft.

Nevertheless, in 1920, the myth held such sway that 'Joan of Arc' was created a saint by the pope.

Joan's father was Jacques Darce. Apparently his name is variously recorded as Darc, sometimes Tarcxe - but apparently never s'Arc, as in the 15th century, the apostrophe was never used in names and there is no such place as Arc from which she could have claimed heritage. Mother Isabelle de Vouthon and father Jacques chose to be known by Romée, indicating that one or both had undertaken a pilgrimage to Rome and were thus entitled to use the name.

In

1412, our 'Joan' was born and christened Jehanette. Apparently it was

not until the 19th century that 'dArc appeared in reference to her, and it was Napoleon who created the beginnings of the story.

Author

Graham Donald cites records found in Notre Dame that were researched by

prestigious French historian Roger Caratini and his summary pointing

out that 'Joan' could not have saved the beseiged Orleans, as the city was never besieged. Further, Donald quotes writings of the author of Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, Dr. E Cobham Brewer, stating that Belgian antiquarian Joseph Octave Delepierre cited a document found in the archives of Metz, later substantiated by family records found in 1740, that showed that Jeanne D'Arcy had married Robert des Armoise, knight, with further receipts and records sproving that Jeanne was very much alive in 1439 - after her supposed martyrdom in 1431.

So why did this lass become our martyr? Apparently to cast abhorrence on the British.

It seems that the love:hate relationship between the French and English has many faces.

Philip - self proclaimed 'The Good'

Someone who is self-labelled 'The Good' caused me to reflect on the habit of nobility to label themselves worthily. This was seldom exemplified better in a lineage than in that of the powerful Duchy of Burgundy.

His biography Philip the Good: The Apogee of Burgundy (The History of Valois Burgundy) is a fascinating story of power, intrigue, illegitimacy, nepotism – and a lavishness in arts patronage that outshone the other courts of Europe during what the French Dauphin, Louis called 'the Burgundian century'.

The father of Philip 'The Good' was John 'The Fearless' – and Philip’s son was 'The Bold' (though history records that this was sometimes wryly replaced by his subjects to be 'The Reckless').These Burgundian kings were anything but modest.

As Napoleon said:

History is a myth that men agree to believe

…and nobility enjoyed the fabrication of such myth.

A courtyard clock: A modern invention

The chapel spire tower is also the clock tower. This is so normal now that it is hard to place this clock in its historical context.

At a time when the main purpose of a clock was to strike the hours, in 1389 a clock in Rouen introduced the striking of the quarter hour.

As time ticked on, domestic clocks were designed as miniatures of the great tower clocks, with weights and pulleys to regulate the hours – until in the mid 15th century the spring-loaded clock enabled transportable clocks – and eventually the pocket watch.

Hospices de Beaune rooftop embellishments

The occupants of the room below the clock Hôtel-Dieu tower must have had ringing in their ears – and one hopes the higher tiny window was not that of a resident.

Even the chimneys of the Hospices de Beaune have character…

I noted the differing chapel roof colours and was somewhat perplexed by why there were so many different sizes of window.

I also wondered about who had peeped out of the tiny windows in the past….

…for they would have had close-up views of the elaborate detail of the spire above, the window beneath…

…and the multiple spires of the chapel roofline.

A truly noble love affair:

The benefactress of the Beaune Hôtel-Dieu

Guignone de Salins was the person who influenced the artistic nature of Hospices de Beaune. She was born into Piedmont nobility and her family had a long history of charitable works.

When Guignone became Rolin’s third wife in 1423 (her predecessors were deceased) it appears that she held great influence with her husband, and it was this influence that reputedly saw the establishment of the Hospices de Beaune.

The bond between the two is reflected in entwined initials in tapestries and floor tiles where the initials appear together with ‘Only her’.

In an era of political marriage and marriage for transfer of power, wealth – and in Rolin’s case – a legitimacy of nobility, this appears to have been genuine affection.

The Golden Fleece and Hospices de Beaune

Rolin was noble only through marriage and by accumulating incredible wealth in the course of his role as Chancellor, he became one of the first twenty-four (25 with the Duke himself) members of the Order of the Golden Fleece, Burgundy’s equivalent to the English Order of the Garter.

This chivalrous group was established by Philip “The Good” to bond his noblemen in sworn allegiance to him – and to exemplify knightly virtues – of which charity was one.

The Order of the Golden Fleece Ordre de la Toison d'Or required the wearing of the collar of the insignia every day – serving as a constant reminder of the sworn loyalty to the Duke of Burgundy.

Given Philip the Good’s infatuation with the Crusades, the order was perhaps inspired by the appointment of the twelve Argonauts of mythology who set out with Jason to find the Golden Fleece.

As there was some commentary about the less than blameworthy activities of Jason and his Argonauts and of their appropriateness as role models for chivalry, the adept Chancellor of the Order, the Bishop of Châlons, gave an official version. This changed the origin of the Order of the Golden Fleece to the fleece of Gideon - the same that in legend gathered the dew of heaven - thus giving some sanctity to the recording of a checkered history.

The term 'Golden Fleece' is still in relative everyday parlance in places such as in the Svaneti region of the country of Georgia where, as was the case once in many parts of the world, a fleece is laid in a lower section of a rivulet to absorb granules of gold washed downriver.

When Burgundy was absorbed into the domain of the Hapsburgs, so too did the Order of the Golden Fleece. Then, following the Spanish Wars of Succession and subsequent claims by both Austria and Spain for the true lineage of the order, there are now branches in both countries.

Despite the dual country base of the order, the letter making the award of this high order of merit to a citizen is still signed – in both cases – by 'The Duke of Burgundy'.

As a member of the Order of the Golden Fleece, Rolin made an extravagant endowment in the Hôtel-Dieu. This was not the only foundation that he and his wife undertook while Rolin used his influence to secure control and amass further wealth through his official activities on behalf of the Duke of Burgundy.

Rolin’s nature was that of controlling every detail of the project at hand – and the establishment of the Hôtel-Dieu was no exception. Noticing the effects of the overly rigorous discipline of the first woman to be charged with leading the nursing sisters, Rolin dismissed her and re-wrote the charter under which they were to work – even describing their uniforms.

The medical reforming founder of Hôtel-Dieu

Instead of limiting candidates to those who would take up a lifetime of religious devotion, young women of good reputation between the ages of 18 and 30 could apply, work there for several years, and then go on to either join a religious order or to marry.

After the death of her husband, Guignone joined the order of nuns founded by her husband’s influence. This order worked with the poor of Burgundy, and Guignone lived out her life in the service of the Hospices de Beaune.

Her commitment must also be seen in context of its time.

Guignone was the wife of one of the most influential and richest families in all of Burgundy – a region that at this time was at the apex of its flamboyant luxury.

The art and lavishness at court of Burgundy exceeded that of France or England and lands spread from Flanders to Switzerland.

Burgundy in this era extended through what is now Belgium to the Netherlands and it is through the patronage of people like Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy – and his influential and wealthy courtiers and ministers such as Nicolas Rolin, that Flemish arts flourished.

Perhaps the decision by Guignone de Salins to renounce what her great wealth could offer her as a life of ease after the death of her husband in favour of her service to humanity, reflects the quotation of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in his book The Wisdom of the Sands

In giving

you are throwing a bridge

across the chasm of your solitude.

Clever politics and clever reforms

at the Hospices de Beaune

At its founding, and even before opening it doors, the Hospices de Beaune became well-known enough for others to vie for its control.

To protect it, Chancellor Rolin was able to secure official relief from taxes and other obligations to the Duke or to other regulatory mandates, and to pass the Hôtel-Dieu to the protection of the church.

The real artfulness of this intervention was in the coupling of this behest to maintenance of complete independence from the interventions of the Church or others. Hospices de Beaune was to be run under the charter Rolin had prepared meticulously himself.

The administration that Rolin set in place was detailed and carefully thought-out: from hiring of priests, budgetary regulations, and rules for acceptance of patients.

Well-read and knowledgeable on many subjects, Rolin ordered that the well should be reserved only for those within the Hospices de Beaune – to keep it a source of unpolluted, fresh and health-giving water.

A long lasting charter and stunning arts

The organisation set in place by Rolin was codified in a Charter under which the Hôtel-Dieu operates to this day.

After Rolin’s death, the Hospices de Beaune were under threat from avaricious church officials who sought to annex its growing wealth. Accordingly, Guignone spent more than five years lobbying French authorities for the original charter to be retained - eventually succeeding.

The Hospices de Beaune therefore owe a great debt to Rolin’s key administrative role in its function – and to Guignone in both its décor in her powerful role as its advocate.

The décor employed the finest artisans and artists of the era, and the main hall was constructed like an upside-down ship, with colourfully decorated cross beams and ceiling.

The cross-beams are securely lodged in the mouths of dragons – with caricatures of well-known Beaune personalities of the era between them…

…and above the altar, shields of noble families.

Following the French Revolution the Hôtel-Dieu was briefly renamed Hôpital d'Humanité and suffered some destruction and even desecration of the grave of its co-founder Guignone, before falling into financial disarray and near destitution.

The decree by Napoleon to reinstate the status of nuns – and the foresight of Rolin in making the Hospices de Beaune independent of private, state, or church financial obligations – enabled the Hôtel-Dieu to be restored to purpose.

A moving black and white movie held in the archives of the British Pathé Film archive shows the Hospices de Beaune still active in 1949, with the nuns, almshouse occupants and bed-patients taking midnight mass in the main hall.

If you ever doubted the value of the

Hôtel-Dieu in fulfilling its charter watch this old Pathé footage:

Historic footage of Hospice de Beaune patients

The chapel had been especially designed to enable bed-ridden patients to attend mass – which they did, as you can see in this film clip.

Many of those filmed appear to be still suffering from war wounds, and many still wear the wartime ‘great coat’ – for obviously the hall’s heating was minimal.

This worn clip is compelling as an insight into an era not that far distant in time and yet an age away in term of general well-being.

There are faces here that tell their own story.

Today the original Hôtel-Dieu is a museum, but the work of the Hospices de Beaune continues in four modern buildings throughout the town– with particular focus on the needs of the aging poor, in addition to more general medical support.

Hospices de Beaune: grand architecture,

good care, fine art,

- well funded by great wine

The work of the Hospices de Beaune continues today and its funding comes from the rpoduct of its estates. Famously known in both charitable and wine circles as one of the great wine events of the world, the Hospices de Beaune Wine Auction has taken place on the third Thursday in November since 1859 - with the exception of bad wine years.

The Hospices de Beaune Wine Auction of today has a worldwide buying audience and in addition to estate wines, has wine donated from the best regional winemakers – the great wine houses of the region.

If, like me, the labels are fascinating but you cannot unravel their stories – here is a brilliant guide to the wines of Burgundy – and an explanation about why many people see the smaller, heritage-seeped family vineyards here as superior to the great estates that seem more “big Business” in Bordeaux.

In 1457 the first acreage of vineyards to support the work of the Hospices de Beaune was bequeathed by a local landowner. In turn, many of the great wine growing houses of the region followed this benevolence until now the estate is around 62 hectares (a little over 52 acres).

This is made up of some 60 hectares (150 acres) of Côte de Beaune and Côtes de Nuits, and a little over 4 hectares (10 acres) of Pouilly Fuissé – wines that have been sought by the courts of Europe, and were much favoured by Thomas Jefferson, who toured the area in 1787 before becoming President of the United States of America in 1801.

To the products of this endowment is now added the charitable contribution of fine wines from regional vintners – including some of the most famous Grand Cru names.This video gives some history of the famous wine auction.

The wines of 2020 were exceptional and carefully produced despite the Covid 19 lockdown, with quality that due to the weather that had not been so ideal in 80 years.

In 2024 there was a very small harvest but it yielded the 4th highest results from the auction.

We await the verdict of each growing year but if you would like to be a part of the great wine auction you can register to make a purchas of even just one bottle by following this link. Register for the Hospices de Beaune wine auction

2020 sales second in history

to the record sales of the 2018 Hospice de Beaune wine auction

Wine in a good cause: in 2018 the charity wine auction of the Hospice de Beaune broke its previous €13mrecord of sales - achieving a total of €14,187,150 (£12.6 million, $16.17m). This is said to reflect the excellent coditions for the 2018 vintage. In 2020 the second greatest sales were achieved in the history of the auction, which was delayed for Covid-related safety literally the day before its usual November date. The sale produced €13,438,700 (£12,169,280 / $13,438,700). The President's Barrel resulted in funds for France's frontline healthcare workers disadvantaged by the Covid 19 crisis.

The sale traditionally takes place by candlelight – and now this is represented by the lighting of the candle at the outset of the auction – and it being extinguished after the last bid.

In 2012 the very beautiful Carla Bruni-Sarkozy awarded the charity barrel of Igor Iankovski to a customer from Ukraine for €250,000. In her role as auctioneer hostess she had previously joked that for €200,000 she would deliver it herself and for €250,000 her husband would deliver it. I wonder if he found that an interesting bit of politics to juggle.

In 2011 the proceedings were chaired by the lovely – and smart – Ines Marie Laetitia Eglantine de Seignard de la Fressange – or as the world finds it easier to say: Ines de la Fressenage.

- a model in her teens

- an ambassador for Chanel

- reputedly the one time muse of Karl Lagerfeld

- business woman and fashion designer

- an aristocrat whose grandmother inherited the Lazard banking fortune and whose mother was an Argentine beauty

Ines de la Fressange seems to exemplify Francis Bacon’s quote that:

The best part of beauty

is that which no picture can express.

Ines de la Fressenage gets my vote as more than a pretty face.

Her style guide to Parisian Chic: A Style Guide by Ines de la Fressange reveals that we have beliefs in common.

Amongst them: An hour sleeping or making love

is better than Botox

The benefits to Hôtel-Dieu

from a Duke's Chancellor

…but I digress and must return to the founders of the Hospices themselves.

Guignone Rolin ensured that art had its place in the Hôtel-Dieu and that those in receipt of the services of the Hospices de Beaune could make a contribution of artworks in place of money.

The result is that everywhere there is beauty.

Although there are frescoes on the ceiling…

…with opulent detail…

…and some wonderful paintings…

…Nicolas Rolin actually preferred tapestries…

… of which there are some magnificent examples within the various buildings.

There are lovely statues in the gardens, one seen here through this gate, which is a work of art in itself…

…and others seen through a less elaborate gateway.

Every detail has the imprint of a careful designer – even the doors…

…with their finely wrought locks.

The famous Van der Weyden Beaune altarpiece

Although it was the polyptych of “The Last Judgement” by the Flemish painter Rogier Van der Weyden that was my introduction to the Hospices de Beaune, it turned out to be the one thing which I didn’t photograph.

However, courtesy of Wikimedia commons and the photographer Paul Hermans, here it is.

Wikimedia: Rogier van der Weyden [Public domain]

My reason for not waiting about to take a photo of this for myself was because it seemed to be the thing which was the main attraction to group after group of visitors.

While I was waiting for them to move onwards I found so much else of interest that the idea faded into that most portable of recepticals: the too hard basket.

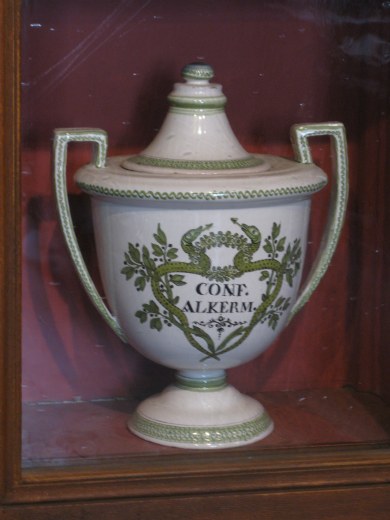

The Hôtel-Dieu Apothecary

I have long been fascinated by apothecaries, and here there are the tools of their trade.

The pharmacy reflects a wide knowledge of many substances to be mixed for one's improved health.

There are the original and beautiful ceramic apothecary jars.

Up close these are even more striking for their quality.

One cannot help but wonder what was mixed or flushed in the marble Apothecary’s sink.

Shakespeare even recognised

the wealth and geographical spread

of ancient Burgundy

It was through Shakespeare I had learned of the great power and wealth of the Court of Burgundy – and some insight into the times when marriage was a political manoeuvre to bolster both.

In Shakespeare’s 'King Lear', the young Cordelia is honest enough to respond that she cannot say she loves her father as completely as her sisters have proclaimed that they do, for she would in the future also owe some of her love to her husband. At the time she was being courted by both the King of France and the Duke of Burgundy.

Taking this as an indication that she did not love her father enough, King Lear disinherited her – with the result that Burgundy immediately withdrew his interest and she married instead the King of France, who valued her honesty.

The very fact that Burgundy was so powerful – actually more powerful at that time than the King – can be best understood in terms of the geography and influence of the kingdom at the time.

The richness of the Duke of Burgundy’s kingdom caused him to have been termed 'the greatest magnate of Europe' – and in this role patronage of the arts became a hallmark of the richness of his duchy.

In this context, the guilds of Burgundy produced the most sought-after art of the period.

Nicolas Rolin and Guignone de Salins brought some of that beauty to heal the souls of the poor while providing a hospital to attend to their physical needs.

Whatever their motives, their long lasting legacy of the Hospices de Beaune echoes the sentiments of Winston Churchill, made in a speech in Dundee in 1908.

What is the use of living,

if it not be to strive for noble causes and to make this muddled world

a better place for those who will live in it after we are gone?