Traditional Balinese Village Wedding

Some travel adventures come from accepting spontaneous invitations, and that is how I came to be a guest at a traditional Balinese wedding in a remote mountain village

Apologies for the quality of the photos that have been scanned from original prints. I shall find the negatives and improve them, but they do evoke the character of the occasion.

On my first stay in Bali I hired a quiet but helpful taxi driver to take me 'out and about' on a daily basis. Like all oldest sons in Bali, he was called Wayan.

I wanted to see beyond the tourist Bali, to explore some of its meaning and real culture – not that of the resort hotels, or of places like Kuta Beach crammed with tourists, persistent sellers of braiding of hair, beach massages and mass produced souvenirs, and where the bars and restaurants get progressively louder as the day proceeds and alcohol levels increase.

Over several days we became quite friendly, and I was duly invited to attend Wayan’s cousin’s wedding. It took a little explanation to assure me that I would not be imposing – but it would honour the family if I came – and if I would take photos.

On the appointed day Wayan collected me and we then drove about 20 minutes to his house to collect his son. His wife and small baby would not attend as the baby was not well and she was very concerned that perhaps this was caused by her not having made the offering to the spirits in the right way the night before.

Off up the mountains we drove – for about another hour, and he explained to me that our destination was a not very wealthy village.

As it turned out, this was an under-statement.

Eventually after passing through many villages and climbing higher up the mountains, we arrived - as usual in Bali, the chickens fleeing before the car as they roam unchecked.

Wayan tied his sarong - and also tied mine over my dress so I was appropriately attired.

He explained that we were there early as he had to help with preparing the wedding feast.

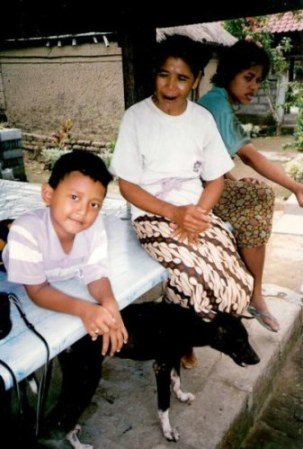

We were greeted by the matriarch, her teeth dyed a dark crimson from chewing betel nut.

She was obviously delighted to see Wayan’s son whom she hadn’t seen for some time, and to welcome me, though thankfully I was not offered any Betel.

The tradition of chewing betel nut in Bali

In former times this would not have been so, as chewing betel-nut was a main social passtime on the island and the first gesture of hospitality.

The process is to take a piece of the green betel, flavour it with lime juice, and then wrap it in a pepper leaf. This is then added to a big wad of chewing tobacco and tucked under the lower lip.

This chewing causes a flow of blood red saliva, and as the beet-chewing addict spits constantly, after the visit of such a betel-chewer, it looks as if there has been a murder.

These days, Betel-chewing is not popular with any but the older generations, for it ruins your teeth and leaves your mouth stained.

However the leaves of the Betel (known locally as sirih) are still boiled and used as a genital wash for women – especially popular after the birth of a child because the liquid causes a shrinking and drying of the tissues – as they say, giving the men more pleasure from sex.

The wretched, ulcerated, and mange-ridden dog that also greeted us is typical of those seen all over the island. They howl in great choruses at night and are thought to keep away the evil spirits – but one’s heart goes out to them in their misery. It has been said that the condition of these poor animals is something that is there to prove that Bali is not totally a paradise.

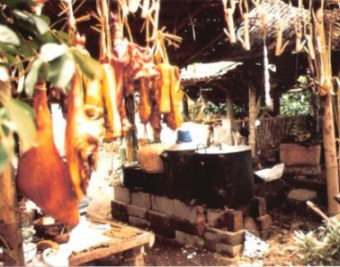

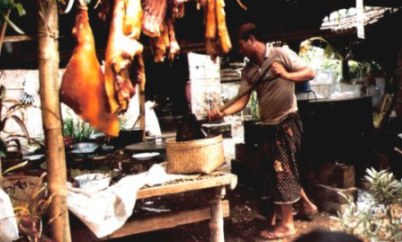

The pork from the pig that had cost the bride’s family a great deal, hung on bamboo hooks.

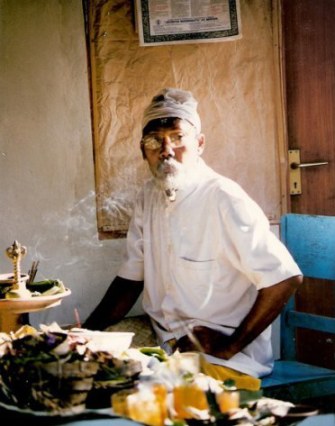

Some of these hooks hand here behind Wayan – still empty and waiting for their bit of pork.

All my alarm bells were set off on seeing this display of pork in the open air in the tropics. I quickly explained that in our culture we do not eat pork unless it is over-cooked and crisp – not an easy concept for a Balinese to grasp.

I was particularly insistent, and Wayan agreed that he would make sure I was served only well-cooked meat.

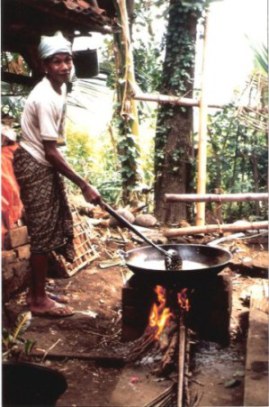

A man was tending the fire underneath a gelatinous, fat-laden liquid that lay in what looked a giant low-sided wide-based pan :

“Soup”, I was told. “Very delicious”.

I had visions of spending the next several months in hospital after undignified results arising from ingesting said soup – and again explained that we cannot process such a rich and delicious soup as our bodies are not used to it.

As we were speaking, the fire started to go out under the

soup.

The cook took a ladle-full of 'soup', threw it on the lagging fire and 'whoosh' – an inferno!

For 'soup' one could fairly translate 'pure pork fat'.

Having declined the soup and explained about the over-cooked meat, in return I was offered some rice dishes, carefully rolled in the hand of the giver and placed in their palm or on a tray for me to take.

As there appeared to be nothing resembling hygiene as we know it, and the rice was being transported from pot …

…to serving basket – with a shovel…

… the visions of hospitalisation returned, but it would have been rude to decline.

During this introductory process I had been drinking a weak and lukewarm tea from an enamel mug.

Mine had been selected from a group of mugs that were used in succession by several people and then rinsed in a hap-hazard way in a chipped enamel basin whose water was not refreshed during the whole festival.

I excused myself and went to the car and got my folk-medicine remedy: apple-cider vinegar. (Forget the American Express card: don’t leave home without it.)

It was in a small bottle and meant for my whole holiday but I drank all of it that day, diluted in increasing quantities of tea.

Apple-cider vinegar is a miracle drug. It seems to neutralise poisons and is good for whatever ails you – but especially good protection against food poisoning – something for which I now seemed to be severely at risk.

The worst that happened to me from eating all this food in conditions of hygeine that would make our well-cared for internal gut bacteria go to war, was that for about five weeks later my stomach growled like a Balinese dog – loudly protesting that I had introduced all this foreign material into my digestive system.

Happily, thanks to apple-cider vinegar drunk capful by capful in a mug of tea, there were no other side-effects.

The cooking pots were all blackened by multi-use…

… and the one for cooking rice was huge.

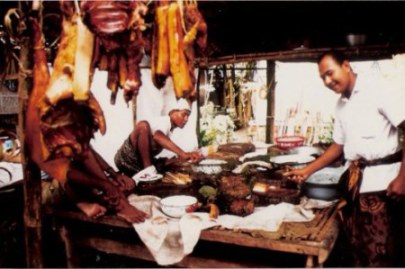

The men were all working happily together preparing different dishes

…and the aroma suggested a delicious feast would follow.

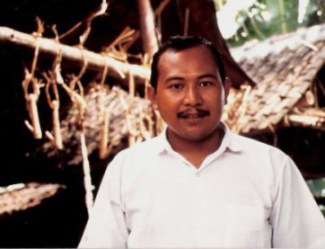

The man on the left seemed to have an air of aristocracy about him -and later in the afternoon, I was to see why.

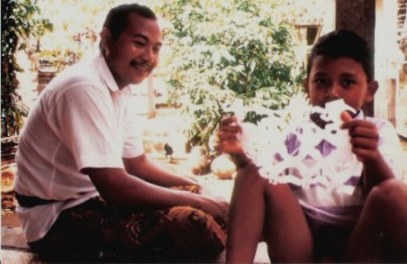

The food preparation took hours and it was a bit boring for Wayan’s son.

Speaking no Indonesian languages, I resorted to an old trick of entertainment by making a cut-out (in this case, torn-out) cowboy with big hat and boots, and smoking a pipe.

Once unfolded from the one image…

…the linked series of paper cowboys had the desired effect.Entertainment is really language-independent with children.

Elsewhere, others were also waiting for the wedding to begin.

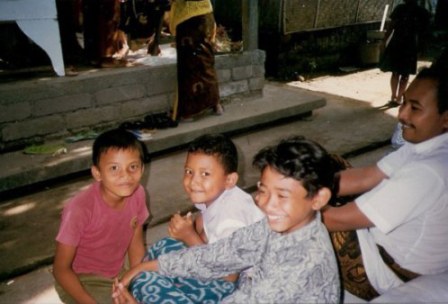

It was obvious that my particular Uncle Wayan (as against all the other first sons with the same name) was a favourite with the youngsters who kept seeking him out…

..but the children were not sure about me, as it appeared that I was the first non-local to have attended a village event.

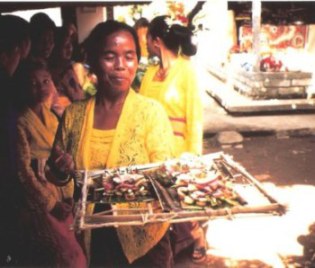

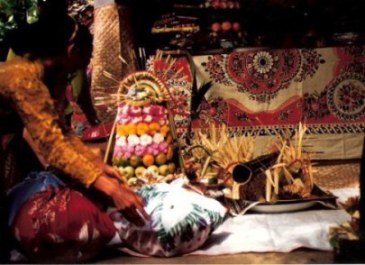

While the men prepared the food, the women were busy placing the appropriate offerings around the area.

Such offerings are crucial to achieve a happy outcome.

The wedding itself eventually began – and the man who had been busy helping in the preparation of food, and whom I thought to look very aristocratic, was the celebrant – apparently the priest or village leader.

In Bali a wedding is a very improtant step. Marriage places you on the social ladder: enabling rights to water and therefore rights to independence of life.

In Bali, to be a married and have a family is vital, for only married men can take part in the village organisation and division of water rights.

Equally important is the belief that only your child can perform the complicated rights that set your spirit free from your dead body so it can be resurrected and not roam as a lost ghost. To prevent such a dreadful fate, some childless couples are given a child from another relative to raise as their own.

A Balinese marriage takes place within the framework of carefully set out rituals that mark a person’s life.

The Hindu tradition is based on has many rituals and obligations of daily sacrifice. The three major ones are Ngotonin– birth, Nganten – marriage, and Ngaben – death.

The Nganten is not just one ceremony, but a process. In many cases the couples elope – for the same reasons as many westerners: economic and to save a big event.

However, in ordinary cases a Balinese Wedding follows the following pattern:

Unlike in the past when the partenrship was arranged, usually in this era, the two people agree that they want to marry. Then the man and his parents go to the family of the woman to ask for her hand in marriage.

This follows first an informal request or Memadik, and if agreed to, is followed by the man’s family being escorted by village elders to the family of the woman. Here they make a formal request or Ngidih - or sometimes called Ngunduh.

This is an important village event, because there are implications for a new couple joining the village unit as a pair. The village leader will discuss residency in the village - and other village elders will discuss family obligations of both families towards the village – and if the woman is from another village, they outline the rights and obligations of the man’s family to her village.

During this step, there is a religious ceremony to accept a new village member and grant the same rights as a local person: This is called Masakapan or Maperebuan

In turn, the woman holds a farewell ceremony at the temple – called Mapamit. Here, she asks permission from her family, from the associations she belongs to, from her ancestors and from the gods they believed in, as well as the spirits and gods of the other village.

It is only then that we come to the ceremony I attended: Ngaba Jaja which literally means 'to bring a present'.

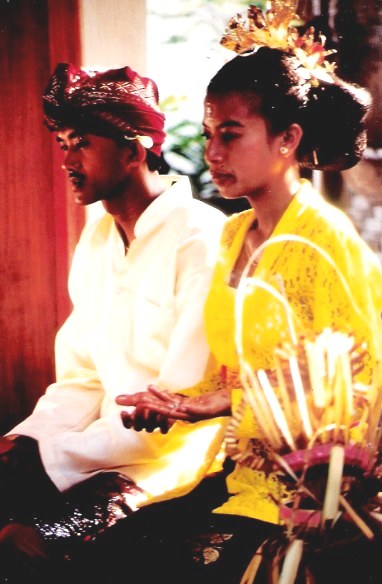

This is a very complicated series of rituals which must be done correctly – hence the extreme concentration of the wedding couple.

The ritual and offerings of a wedding in Bali

The ceremony started.

A Balinese wedding is a bit difficult to follow, although there was a seated audience ready to watch to see that all the rituals were well performed.

The audience included the popular Uncle Wayan surrounded by smiling boys, and me who knew so little about the procedures and traditions, but was a magnet for the youngsters for my novelty.

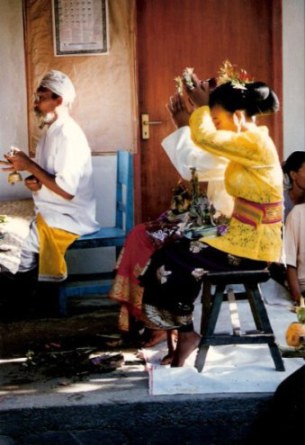

The priest was aided by the parents and the sponsors.

The sponsors have to conduct various rituals using the assorted items gathered beside the priest.

This seemed a complex task.

The bridal pair were obviously concentrating to make sure they did the right thing at the right time.

They were tied with cords symbolising their obligations – to each other, to their family, and to the village.

Paper was spread beneath them, and it was soon obvious why – as cooked rice was showered upon them.

They then received a sort of leaf-parcel of ritual offerings.

These, they accepted in prayer.

It did not appear to be a joyous occasion – and though it is meant to be a religious one, during the whole day there was not a look or a touch that passed between the two that seemed to indicate any level of pleasure from the arrangement.

The only smile from the bride came later with the children…

With the ceremony itself finished, the village brought their offerings to lay on the altar.

One after another of carefully prepared and beautifully wrapped items wer carefully placed in the appointed loaction until there seemed no space left.

The final array was remarkable. Every woman will have spent hours preparing her offerings, just as she does for all ceremonial occasions.

For myself, I gave a carved dolphin, for I had been told this gave a good omen for the future of the couple.

I hope it did.

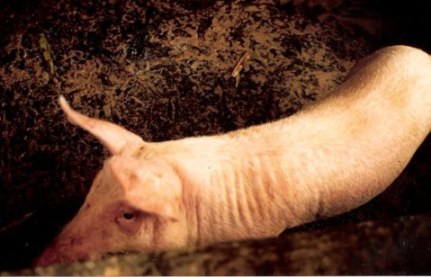

At a mountain Bali wedding the toilet arrangements are shared with the livestock

The inevitable effect of drinking so much liquid took its toll and I needed a toilet.

I was asked anxiously – was it 'only'?

Guessing the implications, and being thankful that it in fact was 'only' – I was directed past a crowing cockerel to a concrete enclosure.

The concrete encolsure was rectangular and open at one end. The concrete was open air and about waist high – allowing a little (but not much) dignity.

The flush mechanism was to stuff back the wad of leaves that formed a plug against the slow flow of water running through a pipe on the top of the wall, and usually stemmed by this stopper.

Hearing a noise in the next enclosure, I saw that I had a neighbour!

In the words of Gilbert K. Chesterton, known to us usually as G.K.:

An adventure is only an inconvenience

rightly considered.

An inconvenience is only an adventure

wrongly considered.

For more Bali pages:

Village of the White Herons